The Friends of the Eric Sloane Museum received permission from the state of Connecticut’s Department and Economic and Community Development to beautify the area between the Kent iron furnace and the Eric Sloane Museum. More pictures will be posted as this project develops.

Our thanks to Lynn Worthington and the Republican-American

Be a part of history – plant an heirloom orchard!

Friends board members Jeffrey Bishoff, Bruce Adams, Mike Everett, Barb Russ, and Jim Mauch tour the grounds of the Eric Sloane Museum on Saturday, January 30th, to scout possible locations for the Noah Blake Orchard. The orchard will contain 10 heirloom variety apple trees, including the Westfield Seek-No-Further, a variety forever connected to Eric Sloane through his book A Reverence for Wood.

We hope you can join us on Saturday April 30th Come and be part of history! Planting of the Noah Blake Orchard in heirloom apple trees, 1-3 p.m. Informal outdoor talk on best practices when it comes to planting and initial care and concerns with heirloom varieties with noted authority Peter Montgomery of Montgomery Gardens. Participants will be invited to help plant small heirloom variety apple trees in the orchard. This will be a free event sponsored by the Friends of the Eric Sloane Museum, but you must RSVP. Please call the Eric Sloane Museum at 860-927-3849 to RSVP for this historic event.

Connecticut heirloom apples to be planted behind Eric Sloane’s recreation of the Noah Blake Cabin

The Friends of the Eric Sloane Museum will be developing programming at the Eric Sloane Museum for 2016, the year we celebrate Eric Sloane and New England Apples. We’ll be exploring many aspects of the apple – Eric Sloane’s treatment of apples and apple trees in print and in oils, apples as an ingredient, apple cider, apples and apple trees in art – the list is magical and we do hope that you can join us for many if not all of our programs and events.

Below is a list of traditional New England heirloom apple trees provided to us by Peter Montgomery of Montgomery Gardens. Peter will help us kick off the 2016 season by planting an orchard behind the Noah Blake cabin on the grounds of the Eric Sloane Museum. We hope you will be able to join us in late April for this historic event!

Cox’s Orange Pippin

Origin: Colnbrook, England, 1825.

Appearance: A yellow background spackled with a little red and a lot of orange in a rustic-looking patina that looks like it came straight off the Sistine Chapel (before the cleaning). The flesh has the cream-yellow tinge of most rich-flavored apples.

Flavor: Think ambrosia salad—pineapple, oranges, marshmallow, and coconut. With lime squeezed over the top. And a sprinkle of flower petals. Cox rarely loses a taste contest.

Texture: The breaking flesh sprays juice upon every bite. With a perfect mix of crisp and tender, and nice thin skin, Cox goes down easy.

Season: Fresh picked in September, it is delicious but tart; by late October, it has mellowed into its full tropical apogee. After that, it goes downhill fast.

Use: Cox would make a fine pie or sauce, but this would be like using the Mona Lisa as kindling.

Region: A staple of UK supermarkets, though often in subpar condition there. Look for it at roadside stands in England, the Canadian Maritimes, New England, the Finger Lakes, the Great Lakes, and the Pacific Northwest. Many feel that Cox only sings in a maritime clime.

Esopus Spitzenberg Alias: Spitz,

Spitzenberg, Spitzenburgh

Origin: Esopus, New York (Ulster County), 1700s.

Appearance: The red coat, spotted with fat yellow lenticels like bubbles in hot oil, makes me think of the hide of some reptilian beast. The greenish-yellow background often shows through. Modestly sizes and modestly ribbed. When it ripens fully, the flesh turns yolk-yellow.

Flavor: Extraordinary brandied, burnt-sugar notes, as if it was already halfway to being a tarte tatin. One thinks of burnt orange, or Cointreau, and (after some mellowing) lychee and roses.

Texture: Excellent breaking crispness. Quite juicy. The skin is on the chewy side.

Season: Pick in October. Give it a month to mellow unless you are a sour fanatic. The flavor takes off around the winter solstice, and will hold in cold storage through spring.

Use: This apple can do anything. Eat it fresh, make it into a pie, ferment it into an unforgettable cider.

Region: The new darling of home orchardists and cider makers throughout the Northeast and upper Midwest.

Wealthy

Origin: Excelsior, Minnesota, 1868. (Crabapple seedling.)

Appearance: Large, round-oblate, with a light red coat over greenish-yellow skin.

Flavor: Middle of the road. Good, sweet-tart, fairly one-dimensional, like a McIntosh without the whimsy.

Texture: So crisp, so juicy when young. It has that odd foamy quality, like modern apples; it seems strangely light and insubstantial, and its cells give way without a fight.

Season: October (September in the South). Get it before it softens.

Use: Fresh eating, sauce.

Region: Northernmost states, especially Minnesota.

Westfield Seek-No-Further (The apple

tree and fruit discussed by Eric Sloane in his book “A Reverence for Wood”).

Alias: Westfield Seek-No-Farther; Seek-No-Further.

Origin: Westfield, Massachusetts, 1700s.

Appearance: You will know it by its lenticels. Like Esopus Spitzenberg, for which it would make a fine body double, it is covered in a dusty red firmament through which its fat, irregular dots seem to swirl like the stars in Van Gogh’s Starry Night. Like many rich-flavored apples, the flesh is yellowish. Sometimes there is a bluish bloom that can be shined away.

Flavor: Sweet and nutty. It displays high apple notes spiked with limey zest, vanilla, and enough astringency to either delight or deter you. This is nature’s apple-walnut crisp.

Texture: Crisp and coarse with a dreamy snap.

Season: Mid-September to early October. Will keep for only a month or so.

Use: Best fresh. Turns mushy if baked.

Region: Rare, but treasured, among New England and Upper Midwest orchardists.

Wolf River

Origin: Fremont, Wisconsin, 1856, near the Wolf River.

Appearance: Massive, round, reddish pink, ribbed, like a Northern Spy on steroids. Inside, the flesh is alabaster, quickly browning when exposed.

Flavor: Hardly sweet, mildly acid, profoundly uninteresting, except right where the flesh meets the skin, where there is a nice hit of cherry.

Texture: Dry, a bit airy, almost spongy.

Season: Early fall for culinary uses.

Use: A baked apple specialist. Also good dried or in pies.

Region: Known nationwide for its size, but most popular in its native Midwest.

Roxbury Russet Alias: Roxbury, Boston Russet.

Origin: Roxbury, Massachusetts, early 1600s.

Appearance: The classic russet, green skin turning the color of oiled oak in the sun, covered in a sandpapery russet. Let’s face it; it’s an ugly apple, although it will sometimes develop a brassy glow on one cheek. Tends toward roundness, though sometimes oval and sometimes squarish. It seems to have a lot of variation.

Flavor: Yummy and strange. Early in the season, its sweetness is almost completely overrun by aggressive, almost painful acid. It’s like biting into a kumquat. By early winter, the acid gives way to a delicious, rich persimmon with nutty undertones.

Texture: Very hard and crunchy at first, Roxbury Russet can turn spongy if not properly stored. Its dense, white flesh is granular and dry, and its skin, like most russets, is thick but not tough.

Season: Pick in October. Gets tastier for several months if stored properly.

Use: Excellent in pies and crisps. Superb keeper. (Store in plastic to preserve moisture.) I love it fresh.

Region: Still highly esteemed throughout New England.

Golden Russet

Origin: Upstate New York, 1840s.

Appearance: A typical green-skinned russet on the shady side, but on the sunny side it turns smooth and truly golden in color, with some copper and bronze and peach mixed in. There are few sights prettier than rows of Golden Russets in the orchard, resembling an apricot sunrise. Look for a smattering of perfectly round off-white lenticels on the skin. Inside, the flesh is pure white.

Flavor: A luxurious delight of pear and fig, a ripe Golden Russet is as rich as it gets. Everything about the sweet, spicy, sprightly flavor says “apricot.” When unripe, the skin has a green pepper note.

Texture: Hard and crunchy, with just enough juice to lubricate your jaw and keep it from overheating. In keeping with the theme, the texture of the skin has an apricot-like roughness.

Season: Pick in October. Don’t press for cider until winter. As a dessert fruit, its flavor peaks in December and January, but it will keep until late winter.

Use: This apple does everything better than most apples do anything.Region: Grown throughout the northern United States by people who are serious about apples and cider.

*Descriptions above were provided by Peter Montgomery – thank you! From “Apples of Uncommon Character” by Rowan Jacobsen

Eric Sloane and New England Apples

Stone Wall Build – Day 1 at the Eric Sloane Museum

The stone wall is amazing. Check out the video shot by board member Jeff Bischoff, who spearheaded the project. Everyone did an amazing job on Saturday, left with new skills and abilities, as well as some new friends and admirers. Now their work is a permanent installation at the Eric Sloane Museum.VID952015050995153748

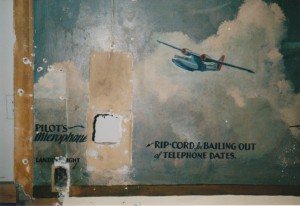

Please help us to document Eric Sloane murals

Readers of this blog know that Eric Sloane painted a number of murals over his lifetime, perhaps his most famous being the one he executed in the lobby of the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. I came across these photographs I took some years ago and thought I would include them here. Readers are encouraged to submit photographs and descriptions of murals known to be executed by Eric Sloane to the “Resources” section of the friends of the Eric Sloane Museum website (www.freindsof

At the time these photographs were taken, the mural pictured had been rescued by some folks at what was being developed as the Cradle of Aviation Museum on Long Island (https://www.cradleofaviation.org). I was invited by Eric Sloane’s 5th wife, Ruth Hinrichs, to view the mural which, if I remember correctly, had just been re-discovered in a storage facility. I believe that the mural was removed by some workers who were dismantling a hanger at the old Roosevelt Air Field. The workers clearly cut it out of the wall – the nominal studs are still visible under the plaster.

The mural encapsulates neatly themes that ran throughout Eric Sloane’s career. It is within this early mural that we can see Sloane’s interest in depicting the past and progress, as well as his playful sense of humor, evidenced by the treatment of the light switch and telephone at the lower left of the mural.

Corroborate and/or enhance Eric Sloane’s work

We’re not only searching for visual connections to Eric Sloane’s life work – sometimes one comes across other sources the corroborate or enhance Eric’s work in some way. If you find references to topics Eric covered in print and in oils in other outlets, please post them here. Below is an interesting reference to bells – specifically to sleigh bells and their distinctive sound:

I recall reading one of Eric Sloane’s books on early American life a passage concerning bells that were placed on harnesses, especially in winter time. The bells were used as a signal to let others know that a horse drawn vehicle was approaching. Presumably, this was done to avoid accidents. Early American lore also posits that one of the roots of the adage “I’ll be there with bells on” grew from the idea that if a driver had difficulty on a journey and required help from a fellow traveler, that driver was expected to present his harness bell strap as a “thank you” to the one who offered assistance. If, then, someone declares “I’ll be there with bells on”, he or she means to suggest that they will reach their destination quickly because the journey will be without incident.

Eric Sloane tells of sleigh bells placed on sleighs for the purpose of signaling the approach of winter travelers. I can speak from experience that driving a sleigh without bells is dangerous. Sloane (as well as my experiences) tells me that sleighs traveling across snow make little noise – noise that is further suppressed by the winer landscape, not to mention the hats and scarves worn by others out in the winter weather. Winter nights could be an especially dangerous time.

Eric Sloane also wrote the neighbors could tell one another from the sound of their sleigh bells. Bells could be purchased by the piece and in various quantities and sizes. Farmers could piece together a custom array of bells that would make a distinctive sound – a personalized horn, if you will. It is wonderful to think of an early American family, gathered around the hearth on a winter’s night, listening to the sound of “Farmer Jones” – or is that Brother Abraham? – gliding by on the family cutter.

I have been reading a fascinating book entitled The Yankee Peddlers of Early America, by J.R. Dolan (1964, Bramhall House, New York). A contemporary of Eric Sloane, Dolan must have shared very similar interests. A passage concerning the peddling of brass bells (page 151), caught my attention and reminded me of Eric Sloane’s writings on the subject of sleigh bells:

“Another item of brass that was sold almost exclusively by the peddler of the nineteenth century was the cowbell. In these days, when a farmer’s pasture is always securely enclosed with wire fencing, a bell attached to the cow is not usually necessary. But in the nineteenth century nearly every cow had to have a bell if she was to be located readily and driven in from the pasture. However the making of cowbells here never reached the point it did in Switzerland, where in certain dairy districts each family developed a cowbell with a distinctive sound that enabled the owner to distinguish his cows from those of his neighbors by the sound of the bell. The bells themselves were sometimes engraved or embossed with a distinguishing mark and since they are virtually indestructible they have become treasured family heirlooms.”

A connection, perhaps, between the early American custom of building custom sleigh bells for a distinctive sound and a similar Swiss practice of locating cows?

– Jim

More Eric Sloane Murals

Here are two photographs I took inside the old International Silver headquarters in Meriden, Connecticut, sometime around 2000/2001. This mural seemed at the time to be in very good condition given it’s age and the likelihood that, like may office buildings of the era, it was populated by a number of heavy smokers. I believe that Eric Sloane painted this mural directly upon the wall. The lights above the main stairwell provided a dramatic effect to Eric’s already dramatic sky.